NO CHANGE, TAKE CHAPPIES!

‘We fucked up some of the biggest armies in the world! Cuba! The USSR! If it wasn’t for us this country would have fallen to communism! Us SANDF okes we stuck together!’, boomed the bar fly from his broken record.

Over the P.A system, a tussle broke out, and a commanding voice echoed through the hole in the wall.

‘Nothing satisfies like the big clean taste than… Chesterfield: Presents, direct from La Rochelle, Johannesburg, with their hit ballad, ‘No Change Take Chappies’, Salazar and the Corner Store Quartet!

The patrons grew silent, and their once puffed up chests deflated. The bar fly dared buzz his wings, and even the Recces, dared let a tooth drop.

After a brief introduction from Carlos from Rustenburg, Salazar approached the microphone, and began his rendition of, ‘The Carnation Revolution will not be Televised’. The baseline swung into action, the flute whispered, and the audience refused contradiction.

‘There will be no pictures of pigs shooting down Samora on the instant replay’

‘There will be no pictures of pigs shooting down Samora on the instant replay’

Among the many vignettes that compose the informal folklore of Johannesburg’s Portuguese diaspora, one story persists with wry familiarity. A child is sent by his mother to the local shop to purchase bread, milk—whatever necessity the day demanded. The bill comes to seventeen rand; he hands over a twenty. But instead of the expected three rand in change, the shopkeeper delivers his verdict—half apology, half decree: “No change! Take Chappies!” And with that, a sticky handful of bubble gum is thrust across the counter in place of currency. The gum’s flavour fades in moments; the sense of having been short-changed lingers much longer.

This anecdote, almost folkloric in its recurrence, is not unique to one household, but is etched into the collective memory of a community suspended between hardship and humour. It is from this shared archive of stories—equal parts injustice and irony—that Adilson De Oliveira draws. His work does not seek to isolate personal experience, but to tap into the submerged emotional registers of a generation born into the ambiguous peripheries of whiteness under Apartheid.

De Oliveira was raised in the southern suburbs of Johannesburg, amidst a tight-knit enclave of Portuguese immigrants. These were not economic opportunists in the usual sense, but displaced men and women—some political exiles fleeing the long arm of Salazar’s Estado Novo in the 1960s; others refugees from the brutal unravelling of empire in Angola and Mozambique during the 1970s. They arrived in South Africa with little more than their faith, their language, and a fierce determination to preserve both.

Yet their presence within the racial taxonomies of Apartheid South Africa was never quite secure. Not entirely embraced by the state’s rigid hierarchy of whiteness, they were often overlooked—offered few protections, fewer privileges. They survived by becoming small-scale shopkeepers, tradesmen, or factory workers; or else, they were conscripted into the SADF to fight “the spread of communism”—a bitterly ironic exchange for citizenship, considering the anti-authoritarian convictions that had driven many of them from Portugal in the first place.

It is this liminal position—between settler and foreigner, citizen and suspect—that gives De Oliveira’s work its tension. The mythology of his community is one of survival, yes, but also of sacrifice misrecognised, of traumas buried beneath jovial exteriors. The men who emerged from these conditions often presented themselves as heroic, industrious, devoted to football clubs and family alike. But beneath that surface lay the corrosive legacies of displacement: frustration, unresolved violence, and, all too often, the numbing routines of alcoholism and domestic authority.

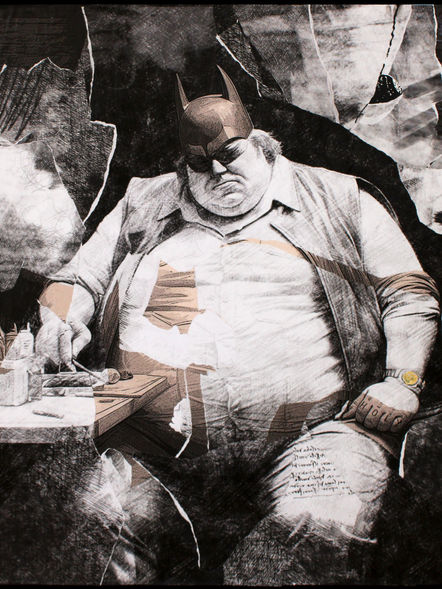

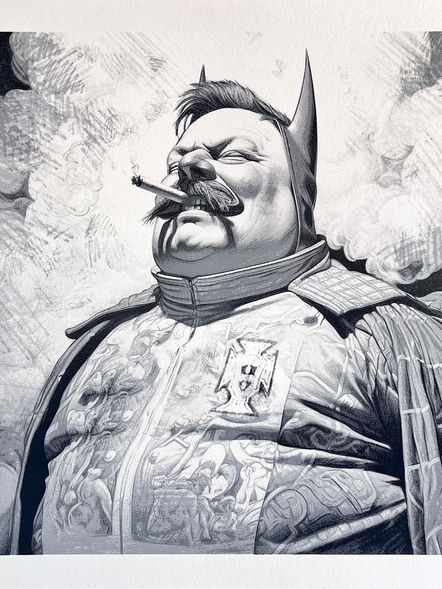

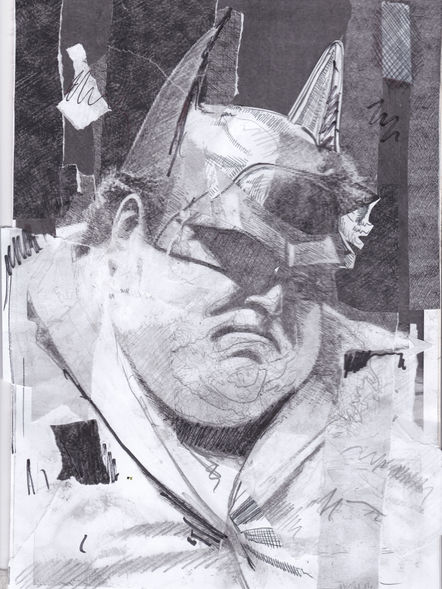

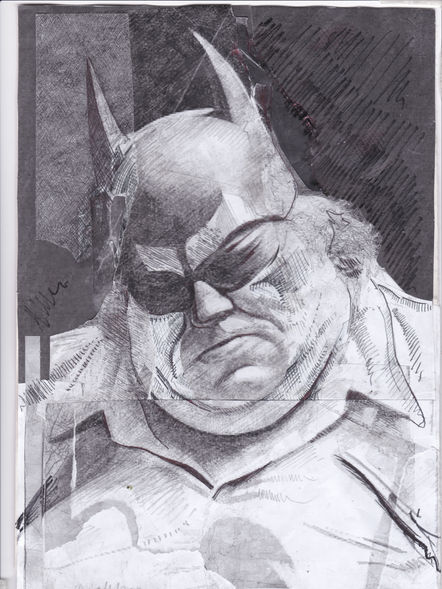

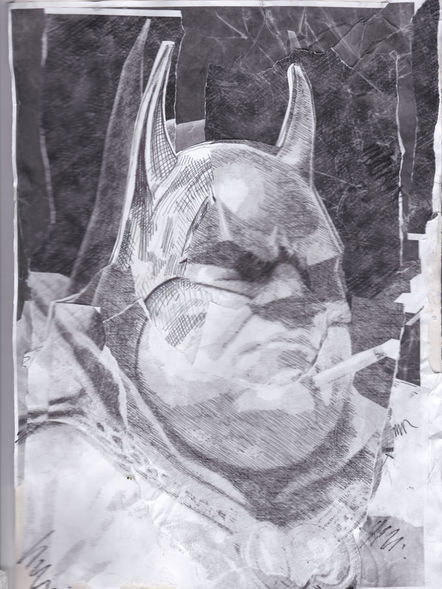

In his recent work, De Oliveira confronts these contradictions through a deft use of satire. His recurring character “Fatman”—a bulbous, low-rent incarnation of Batman—is both comic and tragic. Fatman does not fight crime, but rather slumps in armchairs, gesticulates wildly, or enacts the small tyrannies familiar to so many children of immigrant patriarchs. Here, the language of American pop culture is inverted: the superhero reduced to a figure of bathos, the cape no longer a symbol of justice, but of delusion.

These images begin as drawings—rough, expressive, and suggestive of childhood sketchbooks or underground zines. They are then digitally manipulated, printed, and collaged onto board. But De Oliveira’s interest lies not only in form, but in experience. Through the integration of Augmented Reality—via the Artivive app—the works come alive when viewed through a screen. The viewer is drawn into a multi-sensory encounter: fragments of animation, sound, and gesture emerge, mirroring the fragmented narratives of diaspora memory itself.

In this body of work, De Oliveira is not simply documenting a subculture or offering autobiographical testimony. He is articulating a visual language that holds together loss and humour, tenderness and critique. The gum may have lost its flavour, but its taste lingers—in memory, in irony, and in art.